Inclusive Lending

The Long Road to Fair Housing: How Civil Rights Leaders Paved the Way

January 20, 2025

Homeownership is often celebrated as the cornerstone of the American Dream. However, achieving housing equality has been an uphill battle for many.

The passage of the Fair Housing Act of 1968 marked a turning point, as civil rights leaders like Martin Luther King Jr. and Clarence Mitchell Jr. pushed for reforms that challenged systemic inequality. The Fair Housing Act made it illegal refuse to rent, sell, or finance home purchases based on someone’s race, color, national origin, and religion.

The other protected classes, sex, disability, and familial status were added over the next 20 years.

“The Fair Housing Act was the last piece of the puzzle of extended rights for African Americans, which began with The Civil Rights Act,” said Wade Henderson, senior advisor for The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights and The Leadership Conference Education Fund. “Those two acts were considered the bedrock of a civil rights awakening for the country.”

The Beginning: The Fair Housing Act of 1968

Housing discrimination has long been a persistent barrier to equality in America, denying many families access to safe and stable homes.

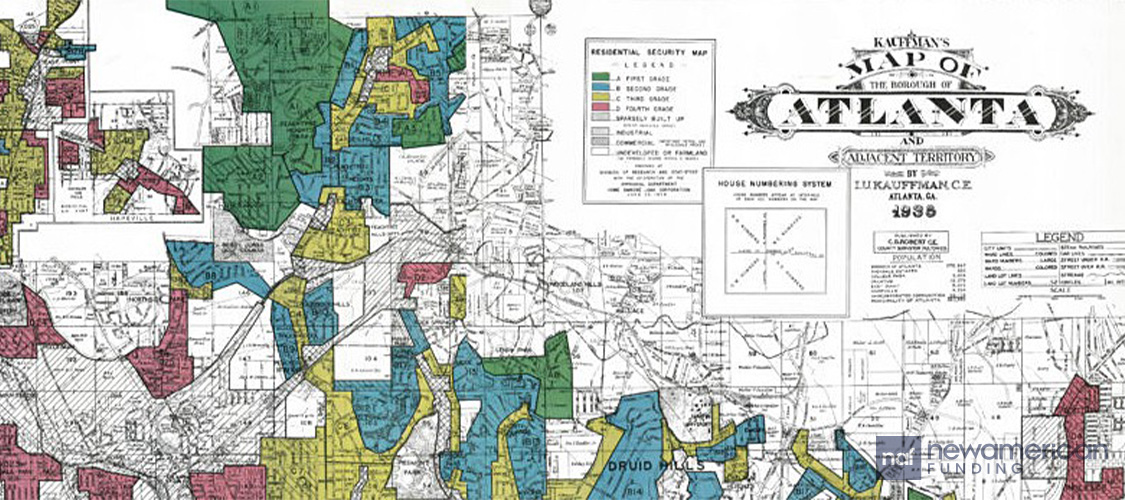

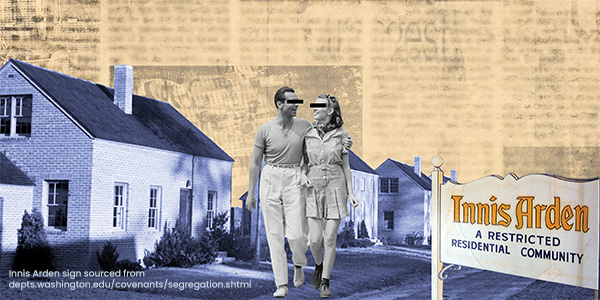

Practices like redlining excluded Black families and others in diverse communities from living in desirable neighborhoods through discriminatory lending and restrictions in deeds that banned the sale of homes to those the developers and local leaders wanted to keep out. This entrenched segregation for decades, reinforcing racial divides.

Martin Luther King Jr. played a pivotal role in the passage of the Fair Housing Act. He advocated for “open housing” policies that challenged discrimination in housing, education, and employment. His efforts brought national attention to housing inequities and galvanized public support for reform.

King’s tireless activism also set the stage for the Civil Rights Act of 1964. This landmark legislation outlawed voting and employment discrimination and segregation in public spaces. It also created the legal foundation for subsequent reforms, including the Fair Housing Act.

Building on this momentum, the Fair Housing Act sought to address discriminatory practices that continued to segregate neighborhoods and deny Black and other diverse communities with equal access to housing opportunities.

Clarence Mitchell Jr., the main lobbyist for the NAACP for nearly 30 years, was known as the “101st Senator” for his work. He was instrumental in advocating for the Fair Housing Act. His strategic efforts helped secure the passage of the act, overcoming significant political resistance.

Signed into law on April 11, 1968, just days after King’s assassination, the Fair Housing Act prohibited discrimination in the sale, rental, and financing of housing based on race, religion, national origin, or sex.

The Fair Housing Amendments Act of 1988

While the 1968 Act was groundbreaking, its impact was limited by a lack of enforcement mechanisms.

“The original Fair Housing Act was largely symbolic without real substantive value because there were no enforcement mechanisms, so discrimination went largely unchallenged,” said Henderson.

The 1988 amendments to the Fair Housing Act introduced stronger enforcement and allowed victims of housing discrimination to file complaints with the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) or pursue legal action.

The amendments also expanded protections for families and those with disabilities, mandating accessible building designs, and addressed senior housing needs. These provisions marked significant progress in ensuring fair housing for all Americans.

(Sex, defined as gender, became a protected class under the Fair Housing Act in 1974. The definition was expanded to include sexual orientation and gender identity in 2021.)

However, despite these advancements, challenges persisted. For example, the “Mrs. Murphy” exemption allowed small, owner-occupied multi-unit properties to bypass certain anti-discrimination rules. An example of this would be a landlord who rents out a room in their home or a separate apartment in their house.

This loophole often undermined the act’s intent and highlighted ongoing resistance to fair housing principles.

Where fair housing is headed

Although substantial strides have been made, the fight for fair housing is far from over.

There were 34,150 fair housing complaints made in 2023, according to the National Fair Housing Alliance. They were made to private non-profit groups, HUD, fair housing assistance programs, and the U.S. Department of Justice.

One ongoing issue is “disparate impact.” This is a legal concept that looks at policies that seem neutral on the surface, but may disproportionately harm underrepresented communities.

This often exposes hidden discrimination, like zoning laws that hurt specific communities.

The journey toward fair housing underscores the enduring impact of trailblazers like King and Mitchell. Their efforts laid the groundwork for progress, but there is still “much work to be done,” said Henderson.

“There are clearly existing challenges to many of the practices we had hoped would become a thing of the past,” said Henderson. “Housing discrimination still exists. Sometimes it’s rampant.”

Smart Moves Start Here.

Smart Moves Start Here.