Inclusive Lending

Hidden in Plain Sight: The Lingering Shadow of Racial Covenants on American Homeownership

February 20, 2025

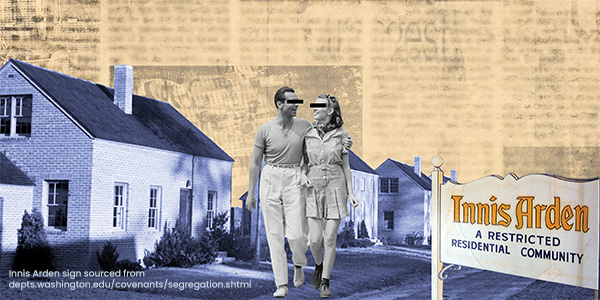

In many American neighborhoods, signs of segregation still exist—hidden in the small print of property records.

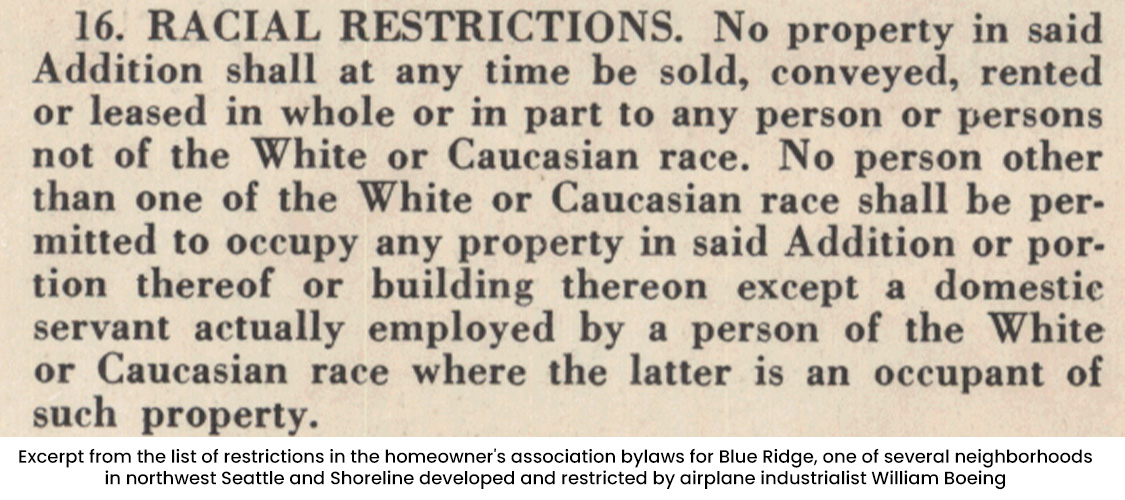

From the early 1900s to the 1940s, it was common for home deeds to include racial covenants that barred Black, Hispanic, Asian, and other groups of people from buying homes in certain neighborhoods. These legal agreements, also known as deed restrictions, were enforced by real estate agents, banks, and even federal housing policies.

These covenants, in addition to redlining and other discriminatory practices, created segregated communities, the echoes of which linger today. Many Black and other diverse families were locked out of homeownership due to these policies. This hindered their ability to build wealth, that could be used to help future generations pay for college and buy homes.

The courts ruled that racial covenants were unenforceable in Shelley v. Kraemer in 1948. They were also outlawed in the Fair Housing Act of 1968. However, these now-illegal covenants remain in deeds across the country.

Experts say these covenants likely exist in every state and just about every major U.S. city. For example, the Mapping Prejudice Project has found over 55,000 homes in Minneapolis that still have these restrictions in their deeds, a lasting reminder of past housing discrimination.

"Segregation is no longer written in law, but it remains written in the land," said Tim Thomas, research director at the Urban Displacement Project at the University of California, Berkeley.

The impact of racial covenants on underrepresented communities

The damage done by racial covenants and other discriminatory practices continues to affect Americans today.

Fewer than half of Black Americans are homeowners today, 46.4%, compared with about three-quarters of white Americans, 74.4%, in the fourth quarter of 2024, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

The wealth gap is also striking. The median wealth for Black households was about $45,000 in 2022—more than double what it was after the Great Recession, according to the Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies, a think tank.

Meanwhile, the median wealth for white households is $285,000, more than six times higher than Black household wealth.

The gap is shrinking. It used to be 11 times higher for white households compared to Black households in 2013.

"The intergenerational wealth effects are very wide-ranging. If there's little or no home equity, it makes it hard to invest in other things like education," said LaDale Winling, associate professor of history at Virginia Tech. Winling specializes in urban and digital history with a focus on housing discrimination and redlining. "The long-term financial impact is severe and continues to shape homeownership rates today.”

Despite these challenges, progress is happening. Since 2011, Black median household income has increased nearly 30%, rising from $41,000 to nearly $53,000 as of 2022, according to the Joint Center. (This is different from household wealth.) That is the highest level in a generation.

How to remove racial covenants from deeds

Many homeowners would like to have these racial covenants removed from their deeds. However, the process of identifying and removing them varies by state and often requires legal action.

In Virginia, homeowners can file paperwork to have racial covenants stripped from their deeds without having to pay fees or go before judge. In other states, the process is more involved.

States like California, Minnesota, and Washington have also enacted laws to make removing racial covenants easier. But the process may still require legal action or court involvement.

Homeowners can learn more about how to get rid of these clauses here.

For those facing more complicated removal processes, organizations like Fannie Mae and the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) offer resources to help.

"These activities in the past have incredibly long-lasting effects on what cities and suburban areas look like,” said Stephen Ross, an urban economist at the University of Connecticut who studies housing segregation and mortgage discrimination.

“They were incredibly damaging—not just to neighborhoods, but to the entire structure of cities, shaping where people live and their opportunities to build wealth,” said Ross.

Smart Moves Start Here.

Smart Moves Start Here.